The Cypriot citizenship by investment programme, commonly known as the Golden Passports scheme, received international attention following an Al Jazeera undercover investigation in 2020 that exposed widespread corruption, leading to its eventual cancellation.

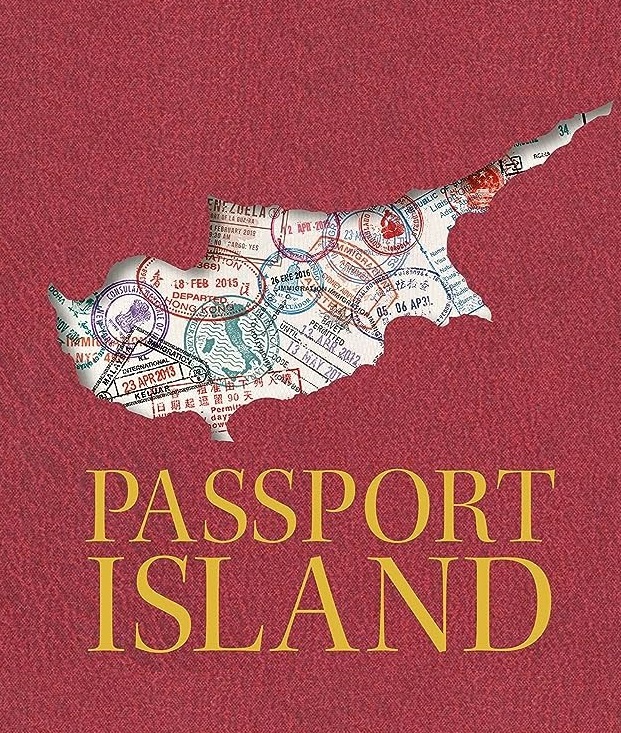

In Passport Island: The market for EU citizenship in Cyprus, published by the Manchester University Press in late 2023, Theodoros Rakopoulos, professor at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Oslo, offers an in-depth analysis of citizenship by investment programmes, with Cyprus as his case study.

In an interview with in-cyprus and philenews, Rakopoulos discusses the unique challenges, insights and findings of his research, noting the social, political and cultural impact of the programme.

What initially drew you to research the Cypriot citizenship by investment programme?

The amazing food of the island, what else?

I am joking: the reason was intellectual and political curiosity about a fascinating phenomenon that encompasses an array of issues (from belonging, to commodification, nationhood, the nature of contemporary capitalism, global inequality, and offshoring) that are irresistibly intriguing.

But also, the food.

In your book, you discuss the commodification of citizenship. How has this programme transformed the meaning of Cypriot citizenship?

One has to read the book to find out, as it is a nuanced process, which might not be easy to spell out in a few words.

But I could say that Cypriot citizenship has always been post-ethnic: being Cypriot is about belonging and relating to the island, regardless of background.

One assumes however that ethnic identification among certain Greek Cypriot leaders and leading professionals tramps civic loyalty to the country.

That is, they did not feel they were “selling out the homeland”, as many told me, given that in their minds the homeland is still the idealized patria of Greece.

This is a conflict between ethnic and civic nationalism: people are concerned about the former, but feel debonair about the latter.

Gaining access to information about this programme can be challenging. How did you navigate the research process for Passport Island?

I am grateful to the people who shared their stories with me. These were primarily the professionals who worked in and with the programme, its “makers”, as I call them in the book: lawyers, accountants, realtors, etc.

I also talked with some of the clients or people interested in acquiring the passport – the “takers”.

Most of the makers opened up to me and sometimes shared sensitive information.

I was also interested in their backgrounds: where they came from, what and where they studied, how they thought about the programme but also politics, the economy, and even life in general.

This is what anthropologists do: we are interested in the anthropoi (humans). And people usually appreciate this.

In your work, you utilise the concept of ‘utopia’. How do you use the concept, and how is it utilised in your analysis?

To be precise, I say “EUtopia”, which is a portmanteau between EU and utopia.

It was clear, from the research, that the clients of the Cypriot citizenship by investment programme were interested in mobility within the EU and potentially Schengen rather than an association with the Republic of Cyprus per see.

We often just take for granted this mobility ease afforded to Europeans with an EU passport – it looks like something “normal” to us, but from a Chinese or Russian perspective it is very different: it is almost utopian.

This is why they are willing to pay a good deal of money to acquire a passport.

Beyond economic benefits, were there any documented social or cultural tensions arising from the influx of programme participants?

Indeed. The main concern of many Limassolians that I interviewed was ecological and related to the quality of life in their urban setting.

They thought that the “passport towers” built to service the citizenship by investment programme were causing a number of environmental and urban problems, from aesthetic to practical.

Add to this the knock-on effect of the high rent prices that people experienced in Limassol at the back of the citizenship by investment programme and its offshoring system.

In my view, however, it is not only the citizenship by investment programme to blame for all this, as it is only the tip (admittedly, an impressive tip) of the iceberg of offshoring services provided to the global elites, which obviously leave a social and environmental imprint on the island and its society.

Do citizenship by investment programmes challenge a world of nation-states, or do they in fact re-enforce it as exceptions for the privileged few?

Some scholars working on this phenomenon would argue the former. According to them, the world is arbitrarily divided and fragmented according to nationality.

I am of the opposite opinion, and the last chapter of my book is a clear analysis of why this must be the case.

In short, the rift in global society is not only across national belongings, but also among social classes.

The intersection of class and nation gives birth to the citizenship by investment programmes as an excellent trick the business world has crafted to serve businesspeople.

To praise it as a liberating mechanism is to pay a disservice to actual social analysis, as it is blind to internal class divisions in the countries of origin -be that Russia or China or others- as well as blind to the perpetuation of a global class system that is only exacerbated by citizenship by investment programmes.

I am willing to change my mind on this, but for now, I have not read a scientifically convincing support for citizenship by investment programmes. My book, the only in-depth analysis of citizenship by investment programmes, is a witness to this.

Some argue that the programme, despite its flaws, was necessary to save Cyprus’s economy after the 2013 crisis. Based on your findings, what is your view?

We must define “necessary”.

We have created an unsustainable economy that relies on the exploitation of the environment (not least through overconstruction to promote the business of real estate and tourism), and on making the island an overbanked hub for financial services that styles banks too big to fail.

If these are the tenets of the economy, then yes, the programme is rendered “necessary”, to fixate with smooth cash flows, a rigged system that collapsed in the 2013 failure.

One whole chapter of my book provides an investigation on the deepening of the Cypriot economy’s offshoring since the 1990s.

To my knowledge, there does not exist another book that looks into this recent economic history of Cyprus, investigating its offshoring component. This is a major focus of the book.

Looking ahead, how do you see the future of citizenship by investment programmes globally?

I think they most probably will flourish and spread. We live in an age where capitalism expands and deepens.

The market increasingly reaches more and more aspects of human life that we were sure it would never reach: from free time and personal thinking to news and entertainment, to health services.

Think, for example, of social media corporations capitalizing on our thoughts and procrastination.

Why not commodify citizenship, if everything is up for sale?