By Evangelia Matthopoulou, PhD in Modern and Contemporary History

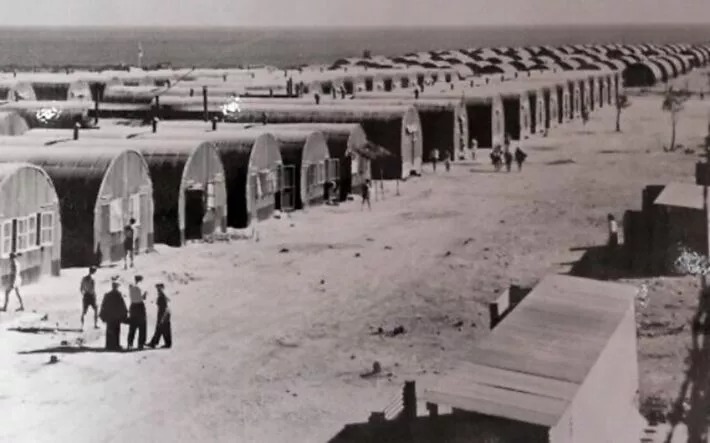

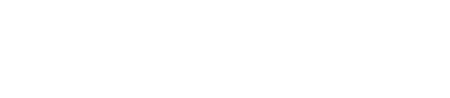

On February 10, 1949, after approximately two and a half years of operation, the camps established by the British in Cyprus as a temporary measure to manage the massive migration of Jews to Palestine/Israel, in Karaolos of Famagusta and Xylotymbou, closed permanently.

Until today, notable academic studies have provided a good depiction of the formation, sociological composition, and activity, as well as the political and economic dimensions of the operation of the detention camps for an unprecedented number of refugees who passed through Cyprus, reaching up to 52,000 (see indicative sources Kutner (2023), Nir (2023), Hadjisavvas (2020), Selioti (2016), Matthopoulos (2016)).

Much less is known, however, about the effective action of Cypriots for the benefit of Jewish detainees. Food and necessities were transported into the camps either under the barbed wire or through workers in the camps, both by Greeks and Turks (Keser, 2009). Often, there was an exchange of goods at the barbed wire between locals and Jews.

Additionally, a complex network of cooperation and solidarity towards the Jews developed, which provided both material assistance within the camps and cooperation in extremely complex clandestine escapes. The characteristic elements of this network included the formation of a “recruitment” core of Cypriots from the base of society, the formation of many different small action groups, mainly composed by members of the Cypriot left, which geographically operated in the area of Famagusta-Deryneia and Larnaca-Dhekelia.

One of the main missions of the groups was the successful transfer of Jews who escaped covertly from the camps to areas where they could find shelter for some time until the day and time of the arrival of a Jewish ship off the coast of Famagusta was determined, where they could clandestinely board with the destination being the neighboring shores of Palestine/Israel.

The Jewish escapees were transported to orange groves of Jews and Deryneians in the Famagusta area, in caves both inland and on the coast, as well as in underground burrows.

Transportation to the Cypriot shores was done by covered trucks, buses, even taxis. Inside the trucks and buses, a very simple arrangement was made, which provided cover for the escapees. In the back of the vehicles, inclined wooden beams and goods were placed, under which the Jews hid to avoid detection. The final stage of the mission was the transfer of Jews to ships off the coast of Famagusta and Ayia Napa.

Usually, the Jews were transferred to these ships by small boats or skiffs. These missions were of high risk. At every stage of the mission, there was a real danger of being intercepted by British blockades and both Cypriot participants and Jewish fugitives being arrested. For this reason, the missions were carried out during the late hours of the night.

The formation of networks

The operation of the networks supporting the escapes of Jewish detainees operated almost simultaneously with the operation of the camps and was largely successful. This is evidenced by both the number of hundreds of Jews who managed to escape to Israel thanks to the support of Cypriots (although there were cases of detainees who, during their escape from the camps, were arrested by the British) and the fact that none of the Cypriots who participated in these missions were arrested, as these missions were kept as a tightly sealed secret among the actors.

To achieve the purpose of Cypriot action, there was certainly a multi-level coordination. On the one hand, at a higher level among Cypriots who knew the English language and could communicate with the Jewish leadership of the camps, mainly representatives of political and military organizations, such as Hagana, and Jewish organizations from the US and UK that coordinated humanitarian, social, and religious work within the camps, such as the American Joint Distribution Committee. These Cypriots were cadres of the left-wing party in Famagusta and Larnaca and were approached from the beginning by the Jewish side.

On another level, the heads of local left-wing organizations acted, mainly in Larnaca, Famagusta, and Deryneia, who were approached by AKEL cadres and were tasked with forming action groups.

In their groups, their fellow villagers or individuals from neighboring villages, who were also members of the left, were included. Both levels of coordination closely cooperated with the island’s Jewish community, which consisted of about 25 families.

Some were descendants of Jewish immigrants who arrived in the early 20th century in rural settlements in Margo and remained permanent residents of the island since then. Others were citrus growers and capitalists who settled in the 1930s mainly in the Famagusta and Larnaca provinces.

The local presence of Jews was very important in the moral and material support of the detainees. They established an informal committee for the care of Jewish refugees and simultaneously played an important role in the regular communication of Cypriots with Jews within the camps. These families were also involved in escapes in various ways, by providing their orange groves for the safe escape of detainees from the camps.

On a third level, there were Cypriots who worked in key positions in the colonial machinery, such as senior officials at the port of Famagusta or in the British army. They were very familiar with the routes of ships, the movements of the British in the wider sea area of Famagusta, as well as the morphology of the coasts where the Jewish ships could approach.

The Profile of Cypriots

In his book “Historical Journey KKK-AKEL Ammochostou, Larnaca 2009,” Theoris Zambas refers to 17 names of members of the Left who participated in these groups. In July 1969, during a memorial ceremony in the settlement of “Nea Salamina” near the camp of Karaolos, at the laying of the foundation stone for the “Garden of Jewish Refugees” square, 20 Cypriots – 18 Greeks and 2 Jews – were honored by the then Israeli ambassador to Cyprus, Tuvia Arazi, for their support and contribution to the escapes.

Approaching this specific aspect of the history of the camps and tracing through primary sources the composition of these groups, new evidence converges on the fact that at least 40 Greeks from Cyprus systematically participated in the groups, among them individuals who were not affiliated with the Left.

Studying the profile of the individuals who participated in the groups, mainly those affiliated with the Left, certain basic characteristics stand out. Firstly, they were men aged 20 to 30 years old. The majority came from the working class layers of Cypriot society, while there were also cases of individuals with higher university education who were responsible for communicating with the Jewish leadership.

Among the rest, some were builders, others were workers in British military warehouses, taxi drivers, bus and truck drivers, fishermen, and owners of orchards. The main groups seem to have come from the Deryneia area and neighboring villages.

The area had significant advantages. Geographically located between the camps of Karaolos and Xylotympou, it offered a secure space for the transit of Jews escaping from both camps.

Both Jews from Karaolos and Xylotympou ended up there. Furthermore, the area had particular morphological characteristics that could serve as a temporary shelter for refugees, such as dense orange groves, underground crypts, and caves. From there, their transportation to specific locations in the coastal areas of Ammochostos, south of the port and east of Deryneia, could be organized more effectively.

Regarding the composition of the groups, it was evidently an area where the Left had influence and from which missions could be staffed. To a lesser extent, individuals from the Larnaca and Dekelia areas also participated.

A significant common element among those who participated in the solidarity network was the fact that many of them came from the ranks of volunteers of the Cypriot Regiment, who fought during World War II on the fronts of Egypt and Italy alongside the Allied forces. Therefore, beyond their origin and political background, which seem to have been the main factors of involvement in these groups, the Cypriot Regiment offered an additional networking mechanism.

Finally, it is worth noting that Cypriot women also made their own distinct contribution to these networks. They facilitated the refugees’ access to food by preparing meals in their homes and by collecting clothing and other essential items.

What were the reasons behind the “Cypriot mission”?

The solidarity action of Cypriots towards the Jewish refugees of the British camps was shaped by both humanitarian and ideological reasons. On the one hand, the creation of the camps and the re-imprisonment of Jews behind barbed wire, after many of them had survived the Nazi camps, was unthinkable for public opinion – not only in Cyprus but even in Britain. On the other hand, in the atmosphere of anti-colonial nationalism, the Cypriots saw a common political goal and a “common enemy” with the Jews.

Both peoples were fighting for their self-determination from British colonial rule. If the Jews succeeded in Palestine, a precedent would be created in the region that would equally favor the Cypriot struggle. For this reason alone, participation in an underground, secretive, and extremely risky mission had special value. It was unquestionably an expression of solidarity with Judaism, which found resonance in the very foundation of society.