The Church of Panagia tou Arakos, which is located in a relatively isolated position in the Troodos mountains near the village of Lagoudera, is one of the most significant Byzantine monuments in Cyprus. With the appearance of this volume, for the first time we have a publication that generously explores all aspects of the building, not only its famous twelfth-century frescoes, but also the later paintings of the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries, as well as its history, its architecture, its icons, its furnishings, its inscriptions, the modern lighting, and not least, its beautifully expressed theology. At the same time the volume is superbly illustrated, with architectural drawings by Richard Anderson and a full photographic documentation in colour of the frescoes by Vassos Stylianou .

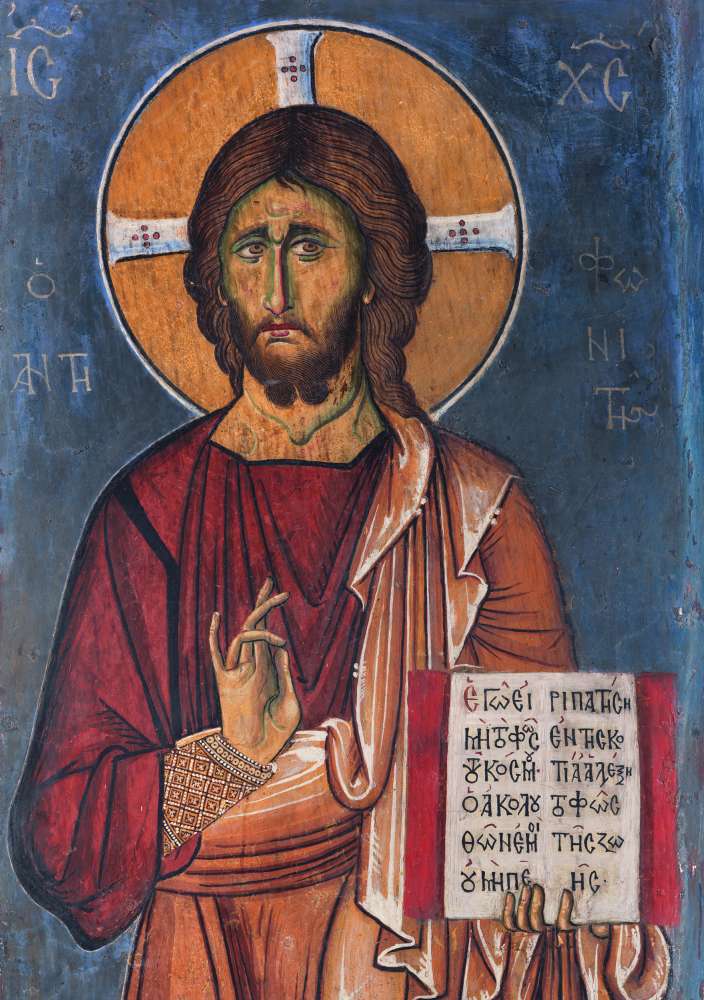

Each of the authors of the individual chapters contributes new insights to our knowledge of the church and its decoration. Athanasios Papageorghiou teases out from the somewhat slender historical records pertaining to the Panagia tou Arakos a coherent and convincing history of the church and its monastery. The architecture is examined by the renowned architectural historian Slobodan Ćurčić; his contribution is a final offering from a distinguished specialist, who died only recently in Thessaloniki in December of 2017. Professor Ćurčić addresses the problems of the phases of construction of the church and considers the evidence provided by the frescoes for the functions of the building, suggesting that it belonged to a monastery that was perhaps founded by the Lord Leon, who is named in the founder’s inscription above the north entrance. Chara Konstantinidi carefully describes and analyzes the twelfth and fourteenth-century frescoes, rightly calling the former “the crowning jewel of Cypriot wall painting”. She unravels the iconographic complexity of the twelfth-century paintings, and relates them to the wider artistic currents of the late Comnenian age, including a new interest in animating the figures through movement and the portrayal of emotions. The many inscriptions on the paintings are presented to us by Panagiotis Agapitos, who explores their purpose and multiple functions within the overall decoration of the church, whether explanatory, prophetic, admonitory, or intercessory. He emphasizes the acoustic nature of the written words, and explains their hierarchy, inspired by Dionysios the Areopagite, which ascends from the earthly admonitions of the ascetic saints portrayed below to the divinely inspired words of the prophets beneath the dome.

The centrepiece of the book is its fifth chapter, an exposition of the theology of the frescoes by the Bishop of Morphou, Neophytos. He shows how the theology of the icon does not exist without its material flesh, that is, its aesthetics. He describes the frescoes as the personal supplication of Leon, addressed to God through the Virgin, and he gives a vivid picture of the painter completing his work in December of 1192, his fingers numb from cold as he works in the freezing church, with the snow already outside. He describes the eschatological program of the frescoes in the dome, which promise the Second Coming, and he characterizes the dance-like energy that moves through the painted figures, comparing it to the breath of the Holy Spirit. Finally, he points out the details of daily life that connect the painted scenes with traditional Cypriot culture, and he also draws attention to the inclusion of many Cypriot saints among the bishops depicted on the walls.

The icons, the iconostasis of 1672, and the seventeenth-century wall paintings are discussed by Chistodoulos Hadjichristodoulou. Among the icons, he includes the two precious portable panels depicting Christ and the Virgin Arakiotissa, which date to the time of the church’s founding, and which until the last century were preserved on the iconostasis. The final chapter, appropriately, is devoted to light. In it, Charalambos Bakirtzis and Ioannis Iliades recreate the original natural lighting of the church, before it was changed by subsequent additions, such as the steeply pitched wooden roof. They discuss the ‘timeless space’ created by the light coming through the doorways and windows, but also the creation of motion by the movement of the sun’s rays around the church. At the end of their chapter, they refer to the recently installed artificial lighting, which is invisible in the best sense of the word. Now, in spite of the enveloping roof and gallery, the frescoes are perfectly illuminated, but in a discrete way, so that there is no awareness of the source of the light. The light is suffused everywhere, with no harsh spotlights or domineering directionality.

So what is the nature of this church, that has been declared to be a UNESCO World Heritage monument, and that has inspired so important and beautiful a book? Why has a relatively small building , hidden in a valley in the Troodos mountains, attracted so much attention?

After an ascent from the dry plains around Nicosia, the Panagia tou Arakos is found in a rugged setting among rocks and pines. The exterior of the building presents a rustic appearance, which does not at all reveal the form of the interior. The steep sloping roof and the wooden portico surrounding the church could almost belong to a stave church in Norway rather than to a monument of Byzantine architecture. The visitor is in no way prepared for the experience of seeing the paintings on the interior. These frescoes are rightly famous, for they are among the most important surviving examples of mediaeval Byzantine painting. They are remarkable, in the first place, because they are so beautifully preserved. Due to the protection provided by the wooden roof, the decoration of the church, with the exception of its western wall, is for the most part complete, from the apex of the dome down to the dado at the floor. Once inside the church, the visitor feels completely surrounded by holy figures; in contemporary parlance, one could describe this as a “total immersion experience”. In the second place, with the exception of the frescoes in the narthex, all of the paintings essentially belong to the same time period, the late twelfth century. Two important icons from the iconostasis also belong to this time. And this was an especially interesting phase of Byzantine painting, for in this period the art of Byzantine churches was on the cusp of a change, engaged with new experiments in the portrayal of daily life, both physical and emotional. Then there is the artistic quality of the paintings, the fluid elegance of their drawing combining with the harmony of their colours. Finally, there is the sophistication of the iconography, which, to use an analogy once used by the art historian Hans Belting to describe another painting of this period, has all the intellectual complexity of a learned sermon. One of the striking features of the book is that the authors of several of the chapters find different theological concepts in the paintings, but there is little overlap between each of their expositions. The paintings can be read and interpreted in many different ways. There is no apparent limit to the range of spiritual meanings that they can provide.

The decoration of the interior of the Panagia tou Arakos recreates a kind of miniature kosmos, reaching from earth to heaven. It can be imaged in the words of a Byzantine poet and rhetorician of the tenth century, named John Geometres, who wrote a short poem describing the church of the Kyros monastery in Constantinople – it was probably the church now known as the Kalenderhane Djami in modern Istanbul. The church of the Kyros, like the Panagia tou Arakos, was dedicated to the Virgin. Addressing the Virgin directly, the poet wrote:

Virgin, Queen of all, your house is heaven….

But you, O Virgin, have set up a well-wrought ladder

Leading up from Earth to the orbit of heaven.

In the Panagia tou Arakos the frescoes create a hierarchy, leading from the mute stones of the earth, represented by the simulated marbles of the dado below, to Christ at the summit of the dome, holding the book of his Word as he gazes down upon mortals. There is a whole universe of ideas contained in the paintings of this small church. For the first time this beautiful book that has been devoted to the Panagia tou Arakos allows us to appreciate all aspects of this remarkable building in their entirety. We are grateful indeed to the authors and the sponsors of the volume for their generous gift.

Henry Maguire

Emeritus Professor of Byzantine Art, John Hopkins University

The presentation will take place in the A.G. Leventis Foundation on May 3, 19:30.

40 Gladstonos Street