Can you imagine George Michael, Cat Stevens or even Lord Adonis saying fishadiko, polishmanos, marketta, banka?

You might as well, as these words belong to the recognised linguistic variety of Grenglish, unique to London’s Cypriot Greek speakers.

Linguists Anna Charalambidou and Petros Karatsareas estimate that there are about a couple of thousands of Grenglish words.

Together, Anna and Petros started the Grenglish Project to document and create a record of Grenglish words and publish a dictionary. On their website, they ask people to submit words as well as stories and visual material about them.

“We are utterly fascinated by how transplanting Cypriot Greek from Cyprus to the UK context through migration has given it a unique shape,” Petros and Anna say.

They explain that in the UK one can find a unique combination of words – mixed with new words and structures that have been borrowed from English – “that are either no longer used in Cyprus or are on their way out.”

Before the First World War, the presence of Greek Cypriots in the UK was limited to around 150 people, according to historian Stavros Panteli. When the British annexed Cyprus in 1914, Cypriots’ political status changed and they found it easier to travel. By the start of the Second World War, there were around 8,000 Cypriots in London.

Cypriot migration to the British capital picked up pace during EOKA’s struggle between 1955-1959. In his book Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain, Robert Winder says that during the four years of conflict, an average of 4,000 Cypriots left for the UK each year to escape violence.

Migration peaked following independence in 1960, with around 25,000 Cypriots migrating in the year that followed and received an additional boost after 1974. Winder reports that “Haringey became the second biggest Cypriot town in the world.”

Today between 150,000 to 300,000 people with a Greek Cypriot background are estimated to be living in the UK.

Petros and Anna say that the first Grenglish words were created as a response to an immediate need for communication. In many cases, the words were referred to an object for which there was not a Cypriot Greek word at the time of early migration. “Many words were created to refer to objects or notions that they first encountered in the UK such as το κέτλον for ‘kettle’, μήτρα for ‘electricity meter’ or η οβερλόκκα for ‘overlocking machine’.”

Others, Petros says, were created to described notions and concepts that were new to them such as ισσούριες for ‘insurance’ or λάλος for ‘landlord’.

The reason Grenglish words sound so familiar to mainland Cypriot Greek, Petros and Anna explain, is that their users adapted them to the phonological and grammatical system of the Cypriot Greek dialect.

“Unlike unadapted switches to English (things like Πότε εννα κάμουμεν lunch break, έππεσεν τ’ αφφάλιν μου! – When are we going on our lunch break, I am hungry!), Grenglish words have become Cypriot Greek in all their formal respects: they have Cypriot Greek endings (λάλ-ος – landlord, μπίλλ-ιν – bill), they have plural forms (τα μπίλλια – the bills) and different case forms (η κορού του λάλου μου – my landlord’s daughter) and, of course, they are pronounced using Cypriot Greek pronunciation.”

Interestingly, some of these words were exported to Cyprus. “We believe that there are some Grenglish words that first developed in the diaspora and were later exported to Cyprus, such as το τάσπι for ‘dustbin’ (but not τασπιέρηες for ‘rubbish collectors’) and μπουκκάρω for ‘to book.”’

Grenglish is now a recognised linguistic variety unique to London’s Cypriot Greek speakers. Nevertheless, Petros and Anna say, many of the contributions on their website came from Cypriots in the USA, Australia and South Africa.

Today this linguistic variety faces the danger of extinction. The Grenglish Project started as an effort to preserve it. “Grenglish is the language of the older generation and is in danger of extinction mainly because of the dominance of English,” Petros says.

“As early as 1990, Natia Anaxagorou identified a ‘process of abandonment that is underway among the second generation”’, which in her view “leaves no space for optimism about the maintenance of the Cypriot dialect in the third and fourth generations,” he adds.

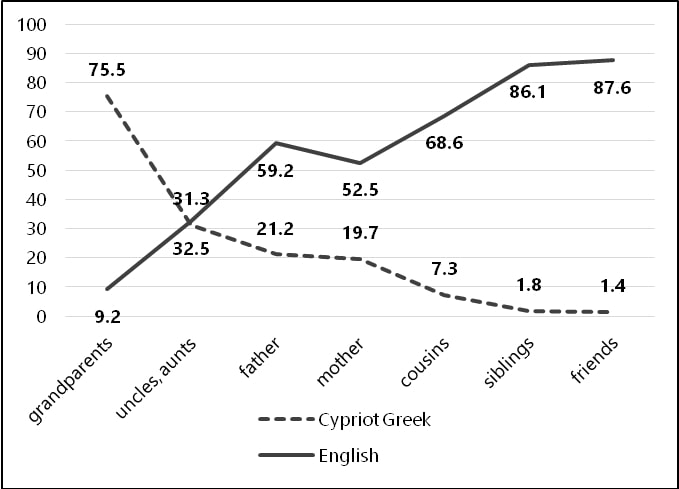

This is backed by quantitative evidence that Andreas Papapavlou and Pavlos Pavlou provided in 2001. They found that UK-born adolescents speak Cypriot Greek mainly with their grandparents, most probably as a matter of necessity as grandparents are likely to have limited knowledge of English.

“The situation now is further shifting towards English, as more and more UK-born Greek Cypriot grandparents have a good knowledge of English,” Petros explains.

Now, a few Grenglish words are used by younger generations and sometimes that happens because speakers do not realise that these words are not part of Cypriot Greek or Standard Modern Greek. “Tellingly, second and third generation British Greek Cypriots report that, growing up in London, they thought that Grenglish words were part of the Cypriot Greek dialect, until they went to Greek school where they were taught the ‘proper’ Greek words,” Petros says.

Another reason that Grenglish is led towards extinction is that it is considered to be inferior to Greek, just like Cypriot Greek in Cyprus is thought as χωρκάτικα (village dialect) when compared to Standard Greek.

“It would seem that Grenglish words are indeed viewed by some as an ‘improper’ or ‘incorrect’ version of both English and Greek, associated with limited access to formal education,” Petros says.

“We’ve heard people describing Grenglish as ‘just mispronunciations, transliterations and adaptations of our uneducated immigrant grandparents who did what they could with the very little they’ve known. Just some silly word creations which fall into the realm of “dad jokes.”

The situation is similar with the language of the Turkish Cypriot community in London, whose members have their own linguistic variety.

“We have been in touch with members of London’s Turkish Cypriot community, who reported a very similar situation: the Cypriot Turkish dialect of London preserving words that are obsolete or considered old-fashioned in Cyprus combined with words borrowed from English,” Petros says.

According to Petros, it is interesting to note that “Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus have the same image of Turkish Cypriots in London as the Greek Cypriots in the two respective localities: that the London communities are somewhat frozen in time, backward, preserving an image of Cyprus in the past in terms of language, tradition and overall ways, not having kept up with developments and progress in the island.”

Both communities even have their words to describe the London communities: “the Greek Cypriots have τσάρληες and τσαρλούες (charlies and charloues), the Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus call London Turkish Cypriots Londres.”

Despite the risk of extinction, Grenglish has started to receive favourable views from young people who view it with nostalgia and associate it with the diversity of their cultural heritage, Petros says.

On Facebook there are pages dedicated to the language, which is also a recurrent theme in the sketches of Cyprus-based comedian and YouTuber Stevie Georgiou.

“We believe that Grenglish words are emblematic of the Greek Cypriot community’s linguistic history and resourcefulness. However, there does not exist a single collection of these words in one place. We want to fill this gap with our project. We want to document as many Grenglish words as we can source from community and leave a permanent record for generations to come,” Petros and Anna say.

One might answer that as the world moves on, some things of the past will be undoubtedly lost. What is the point in trying save a language that is now spoken by a minority within a minority?

Petros responds: “The languages and dialects we speak are part of our heritage. They symbolise our histories and help to enhance our sense of self. Documenting and preserving languages, especially ones that lack prestige or recognition, promotes positive attitudes towards multiculturalism, linguistic diversity and non-standard/new/hybrid varieties.

“In terms of the UK’s Greek Cypriot community, we want to foster positive attitudes in speakers towards their own varieties, and we believe putting them at the centre of our project by inviting them to (re)discover and document their community’s intangible linguistic heritage will help us to achieve this.”

Visit grenglish.org to see Anna’s and Petros’ work and contribute you own Grenglish words to their record.

Also follow them on Twitter at @GrenglishProj.