Decades ago, in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Cordelia Clark ran a restaurant out of her kitchen and parked cabs for her taxi company in her backyard because Black residents were effectively barred from owning or renting store fronts in town.

Now Evanston is poised to be the first U.S. city to offer reparation money to Black residents whose families suffered lasting damage from decades of discriminatory practices.

“It kinda deals with your self esteem. It’s a thing of ‘Am I good enough to stand on my own and say I want to own property here, or I want to cross the redlining?'” said Clark’s great-granddaughter Delois Robinson, 58.

Evanston’s city council will vote on Monday to approve an initial $400,000 round of payments, which will provide $25,000 per family for home repairs, down payments or mortgage payments in a nod toward historically racist housing policies.

The program could become a national model for other cities and states grappling with whether to pursue their own reparations programs. The burgeoning national movement has rapidly gained traction amid a reckoning on racial inequity following the police killing of George Floyd and other Black Americans last year.

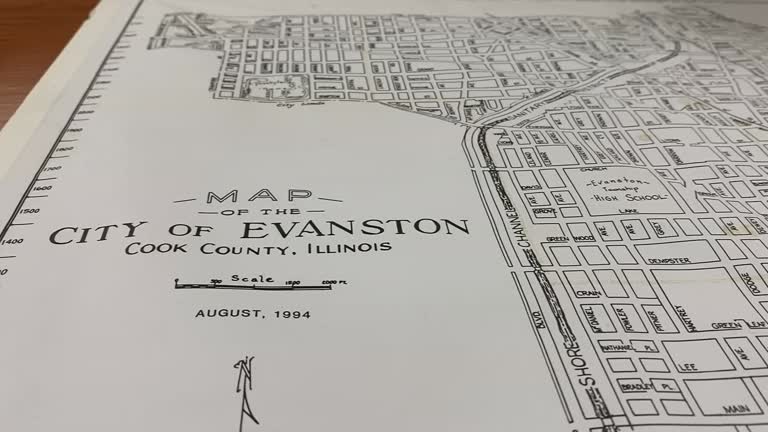

Like many U.S. cities, Evanston once imposed racial segregation through “redlining,” in which banks and insurers refused to serve Black families seeking to live in “white” neighborhoods.

The practice accelerated between 1900 and 1930 when the Black population grew from 750 to 5,000, according to community historian Dino Robinson.

“It was a fast migration and Evanston whites were panicking. ‘What do we do about the Black population coming into Evanston?'” Robinson explained.

“Usually the description of redlining was that it would advise banks to devalue those areas and not invest in those areas, so it would be unwise to do that and primarily because it has a high population of Negroes.”

These days, about 16% of the city’s 75,000 residents are Black, and the impact of those policies persist. The Fifth Ward, where Delois Robinson’s great-grandmother ran two businesses out of her home, is predominantly Black and struggling with inferior infrastructure.

Being the first city to do so places greater pressure, and some Black residents fear that this local step could actually hurt them. Some Black Evanston residents have objected to the plan’s scope and size as inadequate, highlighting the difficulties inherent in designing a program that by all accounts can never fully ameliorate centuries of discrimination.

“It could possibly be the sullying of the true reparations that the United States owes to us. We have no idea what they will do when they come to pay us the real reparations. They might say ‘Oh! You took these $25,000 from Evanston so we’re gonna delete that from what we’re gonna pay you,” said Rose Cannon,

In Congress, a bill that would establish a national reparations commission to study the issue has drawn around 170 co-sponsors in the House of Representatives, all Democrats. President Joe Biden has voiced support for such a commission and could potentially use executive action to create one if the measure fails to pass a divided Senate, as expected.

Other cities, including Chicago; Providence, Rhode Island; Burlington, Vermont; Asheville, North Carolina; and Amherst, Massachusetts, have launched initiatives, though none has yet identified specific funding. California passed a bill modeled after the federal legislation, and lawmakers in New York and Maryland have introduced similar measures.

Private institutions have also announced campaigns. The Jesuit order of Catholic priests last week pledged $100 million for the descendants of its slaves.

But the practicality of implementing reparations programs, especially on a national scale, is still a matter of debate.

Reuters/Ipsos polls taken in June 2020, at the height of racial justice protests, found only one in five respondents agreed the United States should “pay damages to descendants of enslaved people.”

Some opponents ask whether taxpayers can afford to pay out what could be billions, or even trillions, of dollars. Others question how eligibility for such programs would be determined, whether by race, ancestry or evidence of discrimination.

In Evanston, Black residents must complete an application and provide proof of ancestry or that they experienced housing discrimination due to the city’s policies. The initial recipients will be randomly selected if there are more applicants than available funds.

City officials have agreed to devote $10 million over 10 years to the effort, drawn from a new tax on legalized marijuana. Supporters say the funding mechanism is particularly apt, given how devastating the country’s criminalization of marijuana has been to Black communities.

“I’m just grateful and thankful that this is happening, that I’m here alive alive to see it happening. Of course my great grandparents aren’t here, neither are my grandparents, but their offspring are, so we get to benefit from the hardship that they went through,” Robinson said.

(Reuters)