For young Cypriots, war is something they see in the movies. But previous generations actually endured it 49 years ago. How are Greek-Cypriot displaced people coping with this legacy today?

Rodia jumped out of her bed. She was stricken by panic. It was 5:30 am and the sun was rising over the self-housing refugee settlement in Latsia. The sirens had woken her. It took her a few seconds to realise why; she didn’t need to check the date.

For 49 years now, civil-defence sirens installed in 180 locations in Cyprus go off for a minute at 5:30 am each 20th of July to remind people of the moment in 1974 when Turkey invaded the island, and its two communities – Greek and Turkish Cypriots – were plunged into war.

Some psychologists argue sirens should be used only to warn of natural disasters, as their sound can trouble people suffering from war-inflicted psychological trauma.

Dr. Maria Hadjipavlou, a professor of social and political sciences at the University of Cyprus, argues that we Cypriots never talk about our shared trauma. “We hide things under the carpet like they never happened. Many people were displaced, others were injured, saw death or were raped,” she says.

“The fact that the civil society never talks about their experiences from 1974 leaves the historical narrative open for exploitation by nationalist politicians who use it to instrumentalise the suffering, demonise the Turkish Cypriots and present us (Greek Cypriots) as the innocent victims in this situation. If more people understood that we too are responsible for today’s division, they would be encouraged to act to end it.”

There are many untold stories in Cyprus that would surprise us, the younger generations, that haven’t lived through the war and displacement. Stories that we’ve only seen in movies. For us who grew up enjoying one of the highest standards of living in the world, it is surreal to think how close we are to these stories. And yet how far.

We live in a sunny, peaceful holiday resort while still being in open conflict with Turkey. We sip our coffee relaxed at a café in Nicosia, just metres away from a UNFICYP post which stands in the middle of the Greek and Turkish military posts, making the city the last divided capital of Europe and our country one of the most militarised in the world.

Now that almost half a century has passed and given that eight out of ten Cypriots were unborn or under 18 at the time of the war, the sound of the sirens doesn’t unnerve most people anymore. They are used to them.

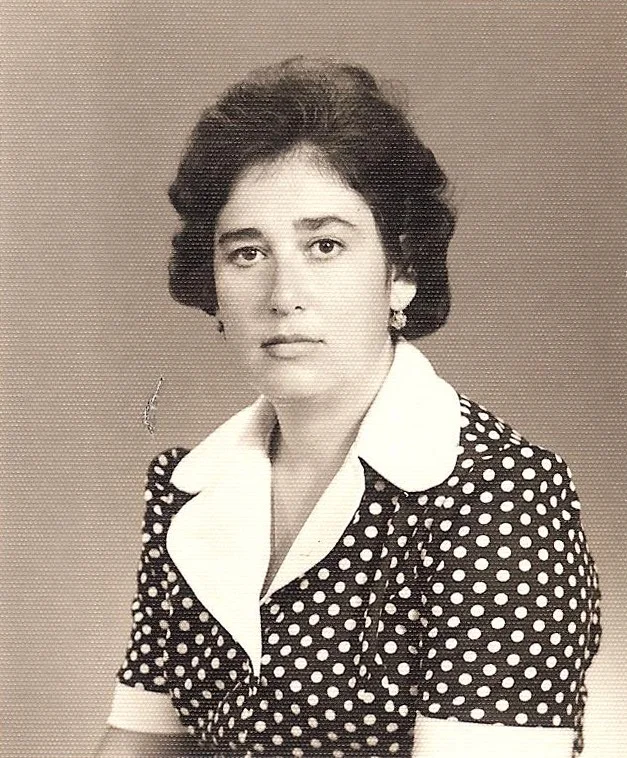

But, for Rodia, it was not so on the morning of the 20th of July 2018. Although she returned to her daily routine after she had heard the sirens, cleaning the house, cooking for her and her son and opening the door to let their cats in, she says that she wasn’t really herself that day.

July 20, 1974

Rodia’s family was prepared the first time they heard the sirens, on Saturday, the 20th of July 1974. “On Friday morning, my brother came from Nicosia where he was working and told us that people were whispering that the Turks will come tonight,” she says.

That day Rodia, along with the other women of the family, were at her home in the village of Dikomo. Four days earlier, a coup d’etat against President Makarios had taken place. The plotters were EOKA B, a Greek-Cypriot right-wing nationalist paramilitary group that supported – enosis – the political union of Cyprus with mainland Greece.

EOKA B enjoyed the material and political support of the junta government in Greece and had hundreds of officers stationed in Cyprus while being involved in the killings of tens of Turkish-Cypriots, as well as Greek-Cypriot leftists.

Although Makarios – Cyprus’ first President after the country gained its independence from the UK – started his political career as a proponent of enosis, he eventually rejected it and favoured the independence of Cyprus. From 1955 until 1974, civil strife was taking place in Cyprus between the Greek and Turkish-Cypriot populations of the island.

At the time, Rodia’s husband was a janitor at the British base in Dhekelia. “When he returned back home at night we told him that there’s going to be a war,” Rodia said. He answered, “I know, the English told us.”

Her daughter, Chrystalla – 10 years old at the time – says that although she and her brother Demetris, could not understand completely what was happening, she “could sense something weird in the atmosphere” from the discussions the grown-ups were having. “We didn’t know what war looked like, we didn’t have a TV, we never went to the cinema to have something to compare it with.”

In the early morning hours of July 20, Rodia and her husband Costas were awakened by the sound of Turkish fighter jets. “We could hear them dropping parachutes. We said, ‘They are coming, the Turks are coming’.”

The family waited until the sun rose and went next door to Rodia’s sister Maroulla, to tell them what was happening. Days earlier, Maroulla’s husband, Kyriacos – who was known in the village as a member of the left-wing AKEL party – was captured and detained by the far-right plotters, who eventually let him and other political prisoners loose when the Turks showed up.

Ironically, things for Kyriacos would have been far worse if Turkey had not invaded, recalls Rodia’s son, Demetris.

Very soon, the plotters realised that besides their internal enemies — the communists and the Turkish Cypriots — they would have to face an external enemy as well, the Turkish military. It became apparent that Turkey would not stand still in the face of the developments.

Turkey issued a list of demands to Greece via an American negotiator. These demands included the immediate removal from the Cypriot government of Nikos Sampson (the president instilled by the plotters after the removal of Makarios), the withdrawal of 650 Greek officers from the Cypriot National Guard, the admission of Turkish troops on the island, equal rights for both populations and access to the sea from the northern coast for Turkey. Britain – a guarantor power for Cyprus’ independence and security after 1960 – declined and also refused to let Turkey use its bases on the island as part of its military operation.

At 5:30 am – hence the timing of the sirens in later years – the first Turkish frigates reached Cyprus at Pentemili beach in Kyrenia.

The first wave consisted of four battalions totalling 3,500 men, 12 M101 howitzers and 20 M113 armoured personnel carriers. Two Cypriot torpedo boats were sent to intercept the approaching Turkish flotilla but were destroyed by Turkish air support. The landing itself did not come under fire.

The provisional government of Cyprus, which was controlled by the EOKA plotters and Greece, were caught completely off guard. Although the Hellenic Armed Forces could track the Turkish movements by radar, they believed that the Turks were bluffing.

In the area the Turkish forces landed, there were two infantry battalions of the Cypriot National Guard nearby. Neither was alerted.

The 281 Infantry Battalion had been previously sent to find Makarios who had escaped from the coup and the 251 Battalion was told to stay put.

Finally, at 08:40 am, Athens, which had a military presence of 950 men in Cyprus, ordered the initiation of a counterattack.

Bedrettin Demirel, the Turkish general who commanded the first wave of the invasion wrote in his memoirs: “I wonder what would have happened if that beach had been mined or if we had faced any obstacles. What would we have done? There was no way we could choose another beach for our landing, there was no time.

Trying to make up for the lack of defence, some civilians took their hunting guns and got on the roofs, trying to shoot the planes, Demetris recalls.

Meanwhile, Rodia’s family remained at home until noon, not knowing what to do. The Turkish planes were drawing closer, a few miles away now. Locals were trying to get some information from the radio but CyBC – the state channel – was controlled by the plotters. In one of Cyprus’ earliest acquaintances with fake news, the channel was broadcasting Greek-Cypriot battlefield victories.

“The radio was not saying the truth. They were saying that our army was shooting down planes and forcing the Turks to retreat. They were saying that we would throw them back into the sea,” Demetris says.

Eventually, the planes started bombing Dikomo. “Next to our house, there was a freshly-sown field. They dropped bombs there and it lit up,” Rodia says. This forced the family to finally leave their house and find refuge under some cypresses. “All the family gathered there, my brothers, their wives, their daughters. We sat under the cypresses.”

Little did they know that it would take them 30 years to see their house again. “We locked the house and left with the clothes we were wearing. We didn’t get any money,” she says.

Rodia’s dad, Yiorgos (Vrakas) had stayed in his coffee shop when the battles started but he eventually joined the family under the cypress trees.

Rodia describes her father as a tall, strong and fair man, who was a respected figure in the village. She recalls how once, Vrakas, came to Nicosia for work and saw some men exploiting a young, “unwashed” orphan as a circus act on Ledras Street. Vrakas confronted the men and took the child under his wing. He eventually became Rodia’s adopted brother, “Ttooulis the barber.”

Vrakas owned the coffee shop at Kato Dikomo’s central square. Most villages had at least two coffee shops, each catering to the differing political ideologies prevalent in Cyprus at the time. Some were frequented by the left-wing, supporters of AKEL and others by the nationalists. However, Yiorgos’ coffee shop served customers from both spectrums of the division.

Rodia says that when they first saw him on the day of the invasion, he was covered in dust and blood. It was the first time she saw her father crying. It turned out, that the dust was debris from his coffee shop, which a plane had bombed but he had miraculously survived.

Eventually, the cypresses proved to be an inadequate cover for the family. “We thought that an open space, like under trees in a field would be better than staying in a building. However, some low-flying helicopters saw us and started shooting. Because it was in the middle of the summer, this field too, lit up very quickly,” Rodia says.

This forced the family to move to the centre of the village. “We could not see anyone where we were, so we went to the centre to see what was going on,” she says. There they found an abandoned warehouse which was full of their co-villagers. Still, there was no sign of the Turks.

They spent the night there.

Flight from Dikomo

“On Sunday morning, a man came and told us: ‘You should go, you should go. The Turks are close to the village,’” Rodia says.

The man was a soldier retreating from the front in Kyrenia, around 20km from Dikomo, Demetris adds. That day, many trucks with soldiers who were forced back by Turkish victories were passing through Dikomo on their way to Nicosia, alerting the villagers to evacuate.

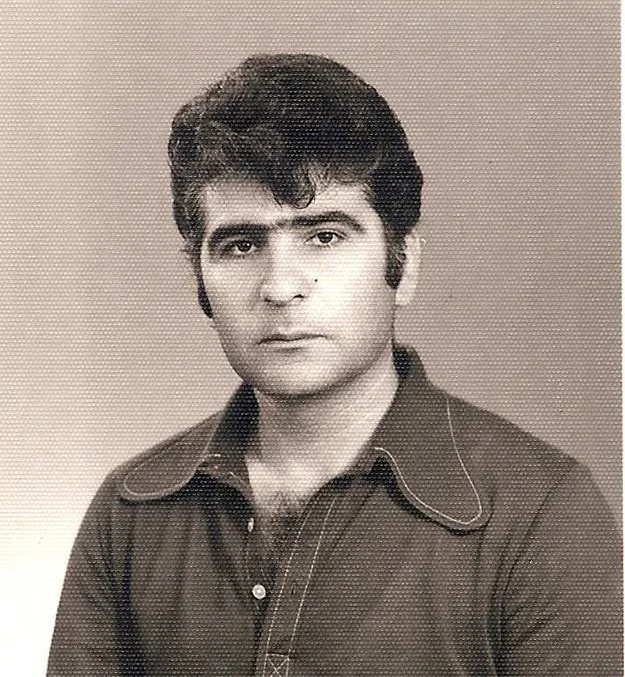

In the rush to escape, the family split up. Rodia, her daughter and her husband got in their car, while Demetris left with Kyriacos and Maroulla.

“We were like caravans with many cars, buses and trucks going to an unknown destination,” says Chrystalla, Rodia’s daughter.

Demetris, who has a big passion for cars now, remembers that, unlike himself, his dad could not be bothered by vehicles. Although he owned a car, he avoided driving it whenever he could, never did any maintenance work on it and always took the bus to work. “It was a very shitty car,” he says laughing.

Costas’ indifference to vehicles backfired in the midst of the war, as the car broke down outside Dikomo, on the way to Nicosia. “After we got out, we saw a truck passing by and the driver let us hop in. He took us to Trachonas, a village 10km away,” Rodia says.

There, Rodia, Costas and Chrystalla spent the night under a tree. “We could hear the planes coming and going, coming and going. They knew that there were people under the trees. They could see us,” Rodia says.

“The next day, a man with a truck came and told us that the ‘Turks captured Dikomo’. We thought that we were going back. My husband told us to shut up because we were never going back. He knew what was going to happen. The Englishmen told him.”

On the 22nd of July, two days after the war began, many cars appeared in the fields in Trachonas. They were people looking for their relatives. Among them was a man from Dikomo who couldn’t find his family.

Costas asked the man if he could take them with him. There was word that the villagers had gathered in Psimolofou, a village to the south of Nicosia, 28km away from Dikomo. The man took them to a nearby village and eventually, after four days, the whole family was reunited in Psimolofou.

“There were many families from Dikomo there,” Rodia recalls. “We stayed in some unfinished houses, without doors and windows. My daughter was crying, ‘I want to go home, I want to go home’ and I was telling her, ‘Don’t cry we’ll go soon’ but Kyriacos started shouting ‘Tell her the truth, tell her the truth, we’ll never go back!’”

Ceasefire

The battles were brought to a ceasefire, on the 23rd of July. Meanwhile, the junta government in Greece collapsed, partly due to the events in Cyprus. Mainland Greek political leaders in exile started returning to the country. On July 24, Constantine Karamanlis returned from Paris and was sworn in as Prime Minister of Greece. He kept Greece from entering the war, a decision that was criticised as an act of treason.

Shortly after, EOKA B-installed Nikos Sampson renounced the presidency in Cyprus and Glafcos Clerides temporarily took the role of President.

The first round of peace talks took place between 25 and 30 July 1974, where James Callaghan, the British Foreign Secretary, summoned a conference of the guarantor powers: Greece, Turkey and the UK. The three countries issued a declaration that the Turkish occupation zone should not be extended; that the Turkish enclaves should immediately be evacuated by the Greeks; and that a further conference should be held at Geneva with the two Cypriot communities present to restore peace and re-establish constitutional government.

On the move again

After a few days of thinking, the family decided to move again. This time to Aradippou, a village near the Dhekelia sovereign base area, where Rodia’s husband was working. This way they could make some money. “When things cooled off a bit, my husband said let’s go to Aradippou. We knew a woman there, she used to be a colleague of my husband’s and she gave us a house.”

Sadly, after a couple of weeks, the sound of warplanes was heard again. By the time the second Geneva conference met on August 14, 1974, international support was swinging back towards Greece. At the second round of peace talks, Turkey demanded that the Cypriot government accept its plan for a federal state and population transfer. When the Cypriot acting president Clerides asked for 36 to 48 hours in order to consult with Athens and with Greek Cypriot leaders, the Turkish Foreign Minister denied him that opportunity on the grounds that Makarios and others would use it to gather more time.

The Turkish Foreign Minister Turan Güneş had said to Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, “When I say, ‘Ayşe should go on vacation’ (Turkish: “Ayşe Tatile Çıksın”), it will mean that our armed forces are ready to go into action. Even if the telephone line is tapped, that would rouse no suspicion.” An hour and a half after the conference stopped, Turan Günes called Ecevit and said the code phrase.

Second invasion

On August 14, Turkey launched its second operation, which eventually resulted in the Turkish occupation of 37% of Cyprus.

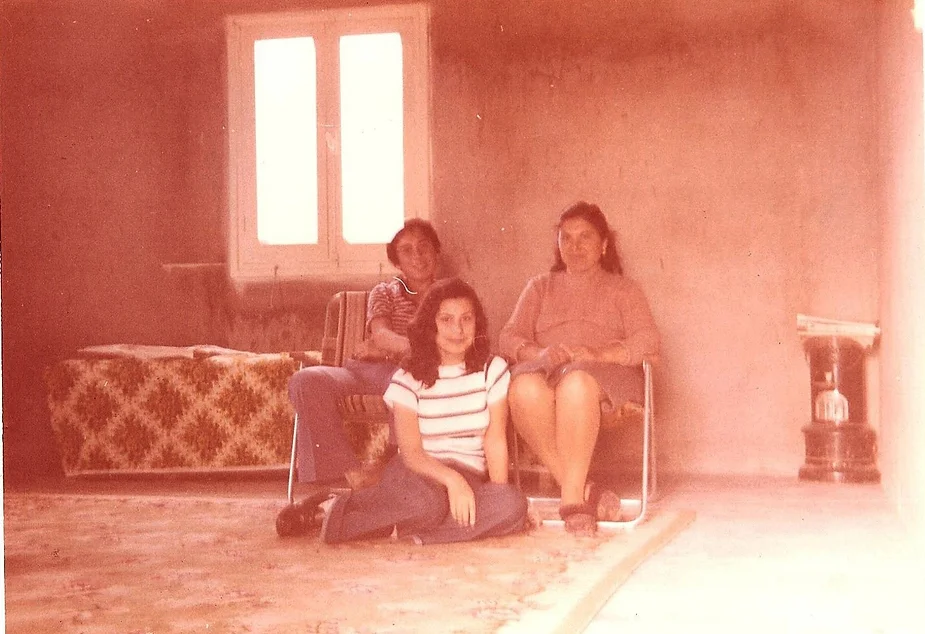

As the planes could be seen in the Aradippou sky, the family was again afraid for their lives. They packed whatever belongings they had left and went back to Psimolofou to find their relatives. Again, they relied on the kindness of strangers for shelter. Rodia says that a local family let them stay in a room in their unfinished house. The owners had left Psimolofou during the first battles and when things calmed down they returned to find Rodia’s family squatting inside.

“We were ashamed, we felt that we were a burden to the people there. I got up very early in the morning to clean up the common toilet and change the toilet roll.” Because the house was unfinished, their room did not have a door. “Me, my husband, my sister, her husband, the kids, my brother, his family, we all lay on the ground in a row. But we could not sleep, the rats walked on us all night.”

Life in the refugee camps

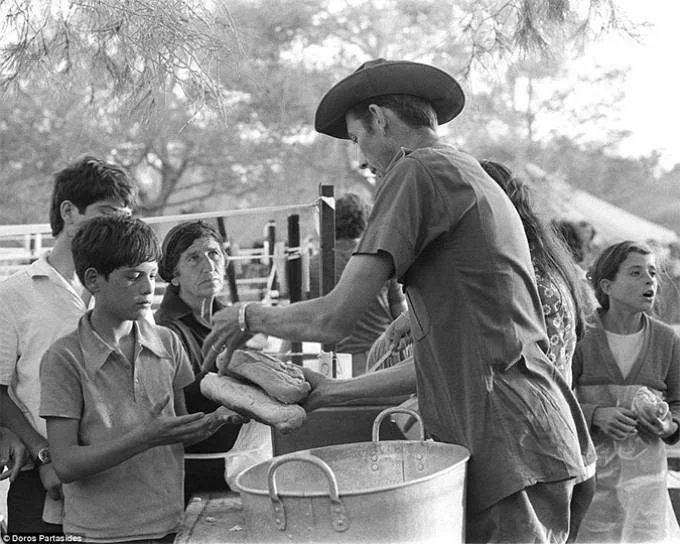

Despite the harsh conditions, the family stayed in Psimolofou for two years. The government, led by the restored Archbishop Makarios, started setting up refugee camps, including one in Psimolofou, which hosted many displaced people. “A family of four would get one tent. If they were more, they gave them another one,” Demetris says.

The family settled there soon. Rodia’s husband, Costas, went back to his old ways of taking the bus to go to work in Dhekelia, while Rodia was rehired in the factory she used to work before the war. “In Dikomo I used to work in a factory where we sew military uniforms. After we settled, the factory opened again near Psimolofou and I started working there.”

She still had to wake up early, but this time to prepare the children for school and get the bus on her own to go to work. Employment brought money and much-needed new clothes.

“I was wearing the dress I left Dikomo with. It melted by all the sitting we did in the fields. When we both found jobs and got our first salaries, we went to Nicosia to buy clothes for the children and us. This was five or six months after the war had begun,” Rodia says.

There were many hardships in the camp. Most had to do with the cold, overcrowding and hygiene. The common toilets and the kitchens were shanties set up by the government. According to Rodia, up to 100 families used each shanty.

However, they were resourceful. Her husband brought back British military blankets from his work. “We slept in camp beds. We would put one blanket below us to be comfortable and use the other one to cover ourselves.”

To avoid the lack of space in the camp’s communal kitchens, Rodia bought her own cooking stove. “I stood in the middle of the tent and cooked with it. We also had a table. We set it up and ate there,” she recalls.

However, what couldn’t be resolved with resourcefulness was the reality of raising two children in a tent. “We were sad. The children were growing up in a tent. But we got through.”

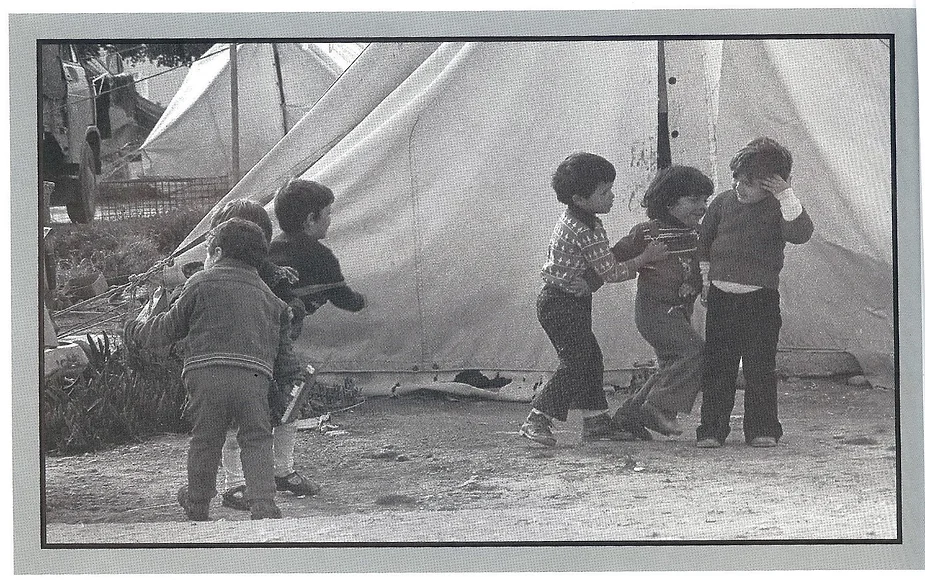

Demetris, though, remembers their time in the camp in a more positive light. He remembers being with his friends from Dikomo and playing all day. “We were having fun. We were rebellious. We did anything we wanted, we didn’t care about school and had no one to check on us.

“At some point, people started having fun. They started doing BBQs, playing music. Most of them thought that we were going to go back to our villages.”

However, what bothered Demetris was the mud. “Every time it rained, the tent would get all muddy and it was extremely cold.”

Some months later – in December 1974, the state started planning how to rehouse the displaced people in the south. Tens of refugee settlements started being built across Cyprus. The government gave people the option either to move into state-built apartment buildings or to receive funding to build their own houses in ‘self-housing projects’.

“There was word that the government was building houses and giving them to the refugees. By that time, we accepted that we would start again from scratch. We accepted that we needed to find a piece of land to build a house on and leave the tents,” Rodia says, with the relief in her voice about escaping life in the camps still evident.

The government gave them 800 Cypriot pounds and some land in Latsia, an industrial area just outside Nicosia, for their new house. Although the amount was not enough to fully fund the construction, Rodia’s family was among the fortunate ones as both parents were employed.

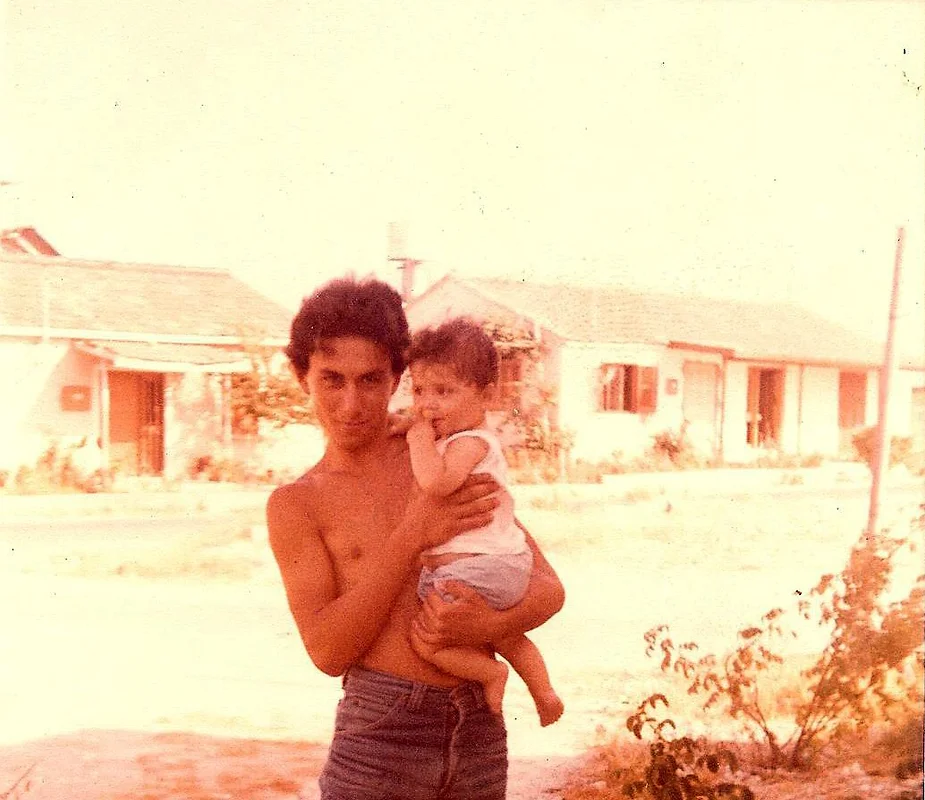

In 1976 the house was finished. “When we came here our soul calmed. We had a piece of land to stay in. We knew it was permanent now,” Rodia says.

Their house was the first one in the neighbourhood. Actually, back then you would not call it a neighbourhood. It was a house among big dirt fields near many factories. The government decided to build refugee settlements near industrial areas, so the refugees could find work there.

Cyprus’ factories are still manned by people living in the settlements. Like Demetris. Others are migrants and some of them are refugees from other parts of the world; Africa, Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

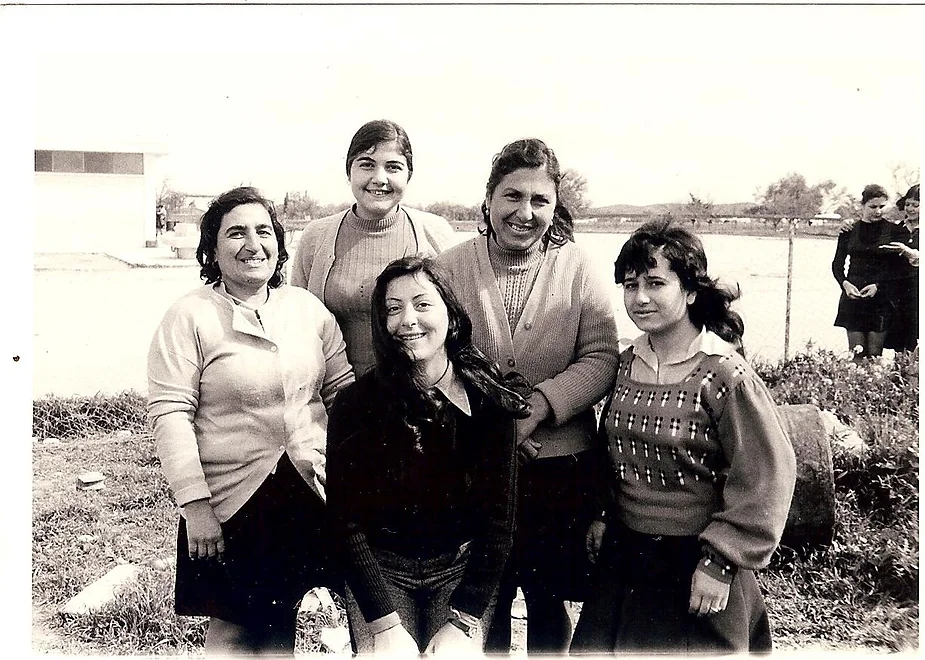

After they settled, Rodia’s daughter, Chrystalla received a scholarship for a private school that offered to weave tuition fees for a number of refugees, while Demetris enrolled in the technical school in Latsia. Rodia found work in a factory that exported clothes to the Middle East, while her husband continued taking the bus to the British base. “After a few years, some other refugees moved here. We mixed with them, we had fun. We got used to it,” Rodia recalls.

Socioeconomic consequences and psychological trauma

The story of Rodia’s family is one that resonates among many families on the island. It is estimated that around 160,000 Greek Cypriots were internally displaced in 1974, around 30% of the country’s population then. Their lives and livelihoods were shattered, while their children and grandchildren inherited socioeconomic inequalities and emotional trauma.

The modern history of Cyprus is a history of loss and of coping. Of restructuring a state out of ruins. We consider ourselves to have been lucky in our own misfortune. How many times do we hear our parents and grandparents say eperasame (we got through)?

A characteristic Greek-Cypriot phrase which contains the memories of a generation. We say that we avoided the worse and when we see the news, we feel relieved that we don’t suffer the fate of other war-torn countries such as Ukraine and Syria. However, the trauma remains.

“Cyprus is a deeply traumatised society,” says Dr. Hadjipavlou. “We avoid talking about what happened then but 1974 can explain many of the socio-political issues we face today. 1974 was so violent and its consequences lasted and still last for so long that it surely shapes the kind of society we are.”

“I think that it is human psychology. You don’t want to talk about the things that traumatised you so deeply. A woman doesn’t want to talk about her rape. A soldier won’t talk about how he killed somebody or saw his comrades dying. It was an unconscious decision, to leave everything behind and move on,” Chrystalla says.

“In the first years, we talked about some things. Mainly about our homes in the village. We wanted to show the non-refugees that we were not always like this. That we too had houses, cars and dignity. But, at some point, we stopped. We felt that we started being miserable and tiresome,” she adds.

Both Demetris and Chrystalla admit that, to this day, they are terrified when they hear the sound of fighter planes. Demetris remembers a day as a teenager in Latsia when he saw a plane flying low and started running to find a tree to hide under.

“When you are a kid you don’t understand that war is something so serious. That life as you knew it ended. For you, life continues normally. We continued playing as we used to. When you are a kid you can live in a hotel or in a tent and feel no difference. You don’t need any luxuries,” he says.

He now recognises the impact the war had on his life and personality. According to him, his life chances would have been much better. “If the war never happened I think that things for me would have been different. It happened at a very crucial, transitional age. Although I was a good student back at the primary school in Dikomo, when I went to secondary school (in Nicosia), I struggled to pass each class.”

Demetris went to secondary school in Latsia. To meet the demands of the growing student numbers – after the influx of displaced people – the school started operating at night as well. In the morning it received the students that lived further away and at night those that lived closer. After his family moved from the tents, Demetris was assigned to the night school.

“After I grew up, I realised that I had made mistakes, but I think that they were mistakes that were not under my control. Sitting down to study while you lived in a tent was a big luxury. There was no space, no lighting, the ground was dirty. The first years in secondary school were chaos. Nobody was interested in education. It was a matter of survival first. The teachers knew what we were going through and couldn’t say something to us if we hadn’t studied. The system pushed you in different directions than education. Our mind was set on other things.”

On her part, Chrystalla admits that she feels traumatised, as she has little recollection of her life before 1974. “The trauma is that gap of memories. For older people, I think that there is only one life, the one before 74. It is like a very long waiting period. It is not life. You just wait for the conflict to be over, so you can go back home. For younger people, there is also only one life. The one after the war. The one before is largely deleted, consciously or unconsciously. It is like you were born as a 10-year-old.”

She says that the war violently terminated her childhood: “We suddenly found ourselves in a situation where we were not the same people as before. The war happened on Saturday and on Monday we were already refugees. Living in tents, having no clothes and relying on others for food. I could have been a different person if it never happened.

“All the things we lived through because of the war and displacement, created a negative mentality in us. Years of insecurity, fear, lack of confidence and uncertainty for the future. There was also the sadness and the misery of the grown-ups that we could feel intensely. Everything was a big black.”

Chrystalla says that she never sought counselling. “There were more serious problems than the trauma of refugees. We had to survive first.”

Rodia says that the kids were not as sad as the adults. But, unlike her daughter, memories from Dikomo return to her mind some days. “My husband got sick because of his sadness. Sometimes I think that if this had not happened he would not have got sick and he would still have been alive. You can’t forget about these things. We will have this sadness until we die.”

Chrystalla says that although no one in her family was directly involved in the battles during the war, many died or faced mental health issues after. “The fact that my father died of an auto-immune disease nine years after the invasion was not a coincidence.”

Rodia’s sister Maroulla, was newly married at the time of the war. “She had a house and she was living a good life,” Chrystalla says. After 1974, Maroulla decided to leave the camp and moved to Greece to stay with her in-laws.

Two years after that she returned to Cyprus, where she lived “in shanties and refugee settlements with no quality of life and with all her relationships destroyed,” Chrystalla notes. Maroulla struggled with health problems and obesity for many years and died of intestinal cancer in 2012.

“Rodia’s mother died in a retirement home, in which the Red Cross had placed her. When we fled Dikomo she stayed alone for a time in the village because we couldn’t bring her with us,” Chrystalla says.

“My grandfather (Vrakas) died in a sanitarium where his grandchildren were employed. It was the only place they could afford to house and care for him, as his whole family was living in shanties and tents, trying to survive. All these experiences create guilt, depression and hardness in people,” Chrystalla says.

Rodia’s sister Despoulla was murdered in the 1980s, a few days after insuring her life in the name of her married boyfriend. The murderer was never convicted and the Hadjidemetris family, being financially and mentally ruined, did not have the courage to pursue the case.

The most recent death in the family was that of Panais, Rodia’s brother-in-law. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and his children said that he often left his home in a refugee housing project in Lakatamia, trying to go back to Dikomo. Once, after days of missing and his story making the news, he was found in a field near the buffer zone. His children speculate that he was on one of his journeys to go back to the village.

As for Rodia, her daughter says that she was never herself after the death of her husband. A hard-working, energetic woman, she started taking anti-depressants every day for the rest of her life. The only time when she was back to her old ways, Demetris says, was when her grandson was born, and she had to take care of him while Chrystalla was working. The war took everything from her, and the grandson was the only thing she had.

Rodia came to show me out as I was leaving her home in the self-housing project in Latsia. I stopped, pretending to be cleaning some leaves off my car to talk to her: “Did I upset you with all my questions Grandma?”

“No son, it was 44 years ago. Praise the lord, these things have passed. I just hope it doesn’t happen again.”

I got in my car and made a U-turn. Rodia was still there, on the sidewalk, waiting patiently, as always, for me to leave her sight as she’d never see me again. Her eyes, just like many old people’s eyes here reflect all of Cyprus’s struggle.

As I leave the house I was born in and the woman who raised me to make my way back to Nicosia, I think about how vastly different our lives have been from those of our parents and grandparents and how many people with stories like this cope silently in Cyprus.

In the memory of Rodia Hadjidemetri who passed away on April 12, 2023.

Bibliography

- Agathangelou, A. and Kyle, K. (2002). In the Wake of 1974: Psychological Well Being and Post-Traumatic Stress in Greek Cypriot Refugee Families. Cyprus Review, 14(1), pp.45-69.

- Asmussen, J. (2008). Cyprus At War: Diplomacy and Conflict during the 1974 Crisis. 1st ed. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Bryant, R. (2012). Partitions of Memory: Wounds and Witnessing in Cyprus. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 54(02), pp.332-360.

- Choisi, J. (1995). The Greek Cypriot Elite – Its Social Function and Legitimization. Cyprus Review, 7(1), pp.36-48.

- Christodoulou, D. (1992). Inside the Cyprus miracle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Drousiotis, M. (2000). EOKA: The Dark Side. 1st ed. Nicosia: Alphadi.

- Drousiotis, M. (2006). Cyprus 1974: Greek Coup and Turkish Invasion. 1st ed. Athens: Peleus.

- Figley, C. (1988). A five-phase treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in families. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1(1), pp.127-141.

- Georgiades, S. (2009). Mental Health in Cyprus. International Journal of Mental Health, 38(2), pp.3-20.

- Hansen, A. and Oliver-Smith, A. (1982). Involuntary migration and resettlement. Boulder, Colo.: Westview.

- Ioannou, M. (2018). Cyprus: 20th of July 1974 – 44 years after! [online] Gr.euronews.com. Available at: http://gr.euronews.com/2018/07/20/kypros-20-iouliou-1974-tourkiki-eisvoli-mauri-epeteios-44-xronia-meta [Accessed 9 Aug. 2018].

- Katsis, A. (2016). Where are the sirens that we hear every year?. [online] city.sigmalive.com. Available at: http://city.sigmalive.com/article/18066/poy-vriskontai-oi-seirines-poy-akoyme-kathe-hrono-eikones [Accessed 9 Aug. 2018].

- Lipton, M. (1994). Posttraumatic stress disorder–additional perspectives. Springfield, Ill., U.S.A.: C.C. Thomas.

- Loizos, P. (2008). Iron in the Soul. New York, N.Y: Berghahn Books.

- Loizos, P. and Constantinou, C. (2007). Hearts, as well as Minds: Wellbeing and Illness among Greek Cypriot Refugees. Journal of Refugee Studies, 20(1), pp.86-107.

- Mavratsas, C. (1997). The ideological contest between Greek‐Cypriot nationalism and Cypriotism 1974–1995: Politics, social memory and identity. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 20(4), pp.717-737.

- Miracle in Half an Island. (1977). The Economist.

- Pierides, M. (1994). Mental health services in Cyprus. Psychiatric Bulletin, 18(07), pp.425-427.

- Pollis, A. (1996). The social construction of ethnicity and nationality: The case of Cyprus. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 2(1), pp.67-90.

- Psaltis, C. (2016). Collective memory, social representations of intercommunal relations, and conflict transformation in divided Cyprus. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 22(1), pp.19-27.

- Refugees, U. (2018). Internally Displaced People. [online] UNHCR. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/uk/internally-displaced-people.html [Accessed 17 Aug. 2018].

- Solsten, E. (1991). Cyprus. [Washington, D.C.]: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress.

- Solomonidou, A. (1997). From Deep – Photoanthology. 1st ed. Nicosia: Cyprus Popular Bank Press.

- Spilling, M. (2000). Cyprus. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark.

- in.gr. (2018). The coup at Cyprus: The events that brought the Attila. [online] Available at: http://www.in.gr/2018/07/15/plus/features/praksikopima-stin-kypro-ta-gegonota-tou-1974-pou-eferan-ton-attila/ [Accessed 17 Aug. 2018].

- Veer, G. and Veer, G. (1998). Counselling and therapy with refugees and victims of trauma. Chichester: John Wiley.

- Volkan, V. (2010). Trauma, Identity and Search for a Solution in Cyprus. Insight Turkey, 10(4), pp.95-110.

- Zembylas, M. (2014). Nostalgia, Postmemories, and the Lost Homeland: Exploring Different Modalities of Nostalgia in Teacher Narratives. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 36(1), pp.7-21.

- Zetter, R. (1991). Labelling Refugees: Forming and Transforming a Bureaucratic Identity. Journal of Refugee Studies, 4(1), pp.39-62.

- Zetter, R. (1992). The Greek-Cypriot Refugees: Perceptions of Return under Conditions of Protracted Exile – Roger Zetter, 1994. [online] Journals.sagepub.com. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/019791839402800204 [Accessed 14 Aug. 2018].

- Zetter, R. (1994). The Greek-Cypriot Refugees: Perceptions of Return under Conditions of Protracted Exile. International Migration Review, 28(2), p.307.

- Zetter, R. (1999). Reconceptualizing the Myth of Return: Continuity and Transition Amongst the Greek-Cypriot Refugees of 1974. Journal of Refugee Studies, 12(1), pp.1-22.

- Zetter, R. (1991). Labelling Refugees: Forming and Transforming a Bureaucratic Identity. Journal of Refugee Studies, [online] 4(1), pp.39-62. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jrs/article/4/1/39/1549129 [Accessed 14 Aug. 2018].